Engineering velocity: Part 2

Your team seems slower... Here's what to do about it.

Last time we covered a lot of reasons why that once-fast team has slowed down. If you haven't read that part already, you should, but to give a quick recap, those were:

- They finished the fast part

- They're swimming in a bigger pond now

- They were successful

- They're still good, it's just the perceptions that have changed

This time, we'll talk about what you might be able to do about it.

They finished the fast part

The first 80% is always the fast part, right? It's just the Pareto Principle in action: You get 80% of the benefit for 20% of the overall effort. But the rest takes 80% of the total effort -- and time. Which people notice. So the paradox is that while the team is now putting in more effort, people are seeing less output.

Shifting how you approach demonstrating value can help here. Instead of demonstrating things being delivered, try to shift to demonstrating problems being solved.

Early on, it's easy to show the tangibles the team is delivering. But that inevitably slows down as the project matures. Teams find themselve spending more time solving more complex problems, with less visible forward momentum.

It's not that progress isn't happening, it's that it's not visible. Make it visible. Enlist a designer to help illustrate the problem. Have a product manager help build a timeline showing the invisible capabilities that have been delivered. Talk through the systemic issues that have been worked through. In short, shine a spotlight on the the hidden work and bring it out of the shadows.

They're swimming in a bigger pond now

As a project matures it always seems to connect more and more to a larger ecosystem. Maybe the work gets so big it gets split across multiple teams. Maybe it becomes a platform other teams are building on. Maybe it comes to rely on a platform itself. Maybe they just have more APIs they're relying on for more features. No matter what the specifics of the story may be, the outline is the same: this work is part of a larger whole.

Which means you now have a hand-off problem, which goes something like this:

- On November 1, Team A decides they want to do

small-thing, so they add it to their next sprint, starting Nov 11. - About a week in, around Nov 19, they realize they can't complete

small-thinguntil Team B doesother-thing. Team B says "Hey, no problem, we'll add it to the next sprint!" - But Team B's sprint just started on the 18th, so their next one won't start until December 2.

- And then, in sprint planning, a senior engineer pipes up to say "You know we can't complete

other-thinguntil Team C resets the config on the thingModulator." - So now it bounces over to Team C, who thankfully get it into their next sprint, starting December 9. They get the config change done quickly so it can get back to Team B, just in time for their December 16 sprint.

- Team B also gets the work done quickly, as promised, in time for Team A to finally do

small-thingin their next sprint -- which is a holiday sprint starting Dec 23.

And that's how a bunch of teams can work really hard, really quickly, and really concientiously, and yet it takes more than eight weeks to get small-thing done. And there's not a whole lot you can do about it.

But you can try:

- identifying dependencies as early as possible. Long before the story is about to go into a development sprint. Track them, get them done as part of the work (and again, show and demo that work as it gets done).

- Aligning sprint start dates across teams can help. Sometimes.

- Lobby for config changes and small dependencies to be handled as they arise, either kanban-style, or by keeping some capacity within the existing sprint cycles.

They were successful

If a project is successful, it grows. As it grows more eyes are on it, and more demands are made. This is another case where the team has to show all of the work they're doing, that includes the less-visible work, as discussed above. It also includes making their priorities very clear and public. If Stakeholder A isn't getting what he wants because all of the efforts are on Stakeholder B's initiative, everyone involved should see that trade-off.

If a project becomes really successful, it might develop into a platform other applications and teams rely on. Which means they're slow by intent. Platforms optimize for reliability and stability, not speed. For a small project, application, or site, it only has to work for a small group. For a platform, it has to work for every consumer and team in the ecosystem.

Just the layer between the platform and the application teams building on it can be a source of slowdowns. For application teams leveraging the platform, enhancements depend on the platform team implementation timeline. For the platform team every deprecation and migration is an exercise in waiting for all the application teams to upgrade -- and that happens at the pace of the slowest team.

They're still good, it's just the perceptions that have changed

We've already covered how teams often fail at highlighting all the progress they're making, which in turn feeds the false perception that they're slower than they used to be.

The irony is that false perception can actually make the team truly slower. It goes like this:

- Over time the team natually picks up tech debt, bugs, and hidden work.

- Like most teams, they don't do a great job of showing that work.

- People start pushing them to "increase velocity."

- The team responds by prioritizing quick wins, which means they're not focused on bug fixes and work that enables more meaningful forward momentum.

Which means they end up slower than they were before they started. It's like a company so focused on short-term earnings that they don't do the hard work of staying in business (GE is a great recent example).

Show the work

If there's one takeaway here, it's that good teams usually don't get slower as they mature, they get more complex. In complex systems sometimes you go slow now because it will make you faster later. Sometimes you're not going slow at all, but people aren't seeing all that's happening. In either case, illuminate them.

“Velocity” can mean a lot of different things depending on the context and who's throwing it around. It's like a hex, and the best defense against the dark arts is the bright light of day. So never fail to shine a light on the work.

The big exception is platform teams, which are slow by intent, but even then, they're enabling application teams to be faster. Show that.

Show the work.

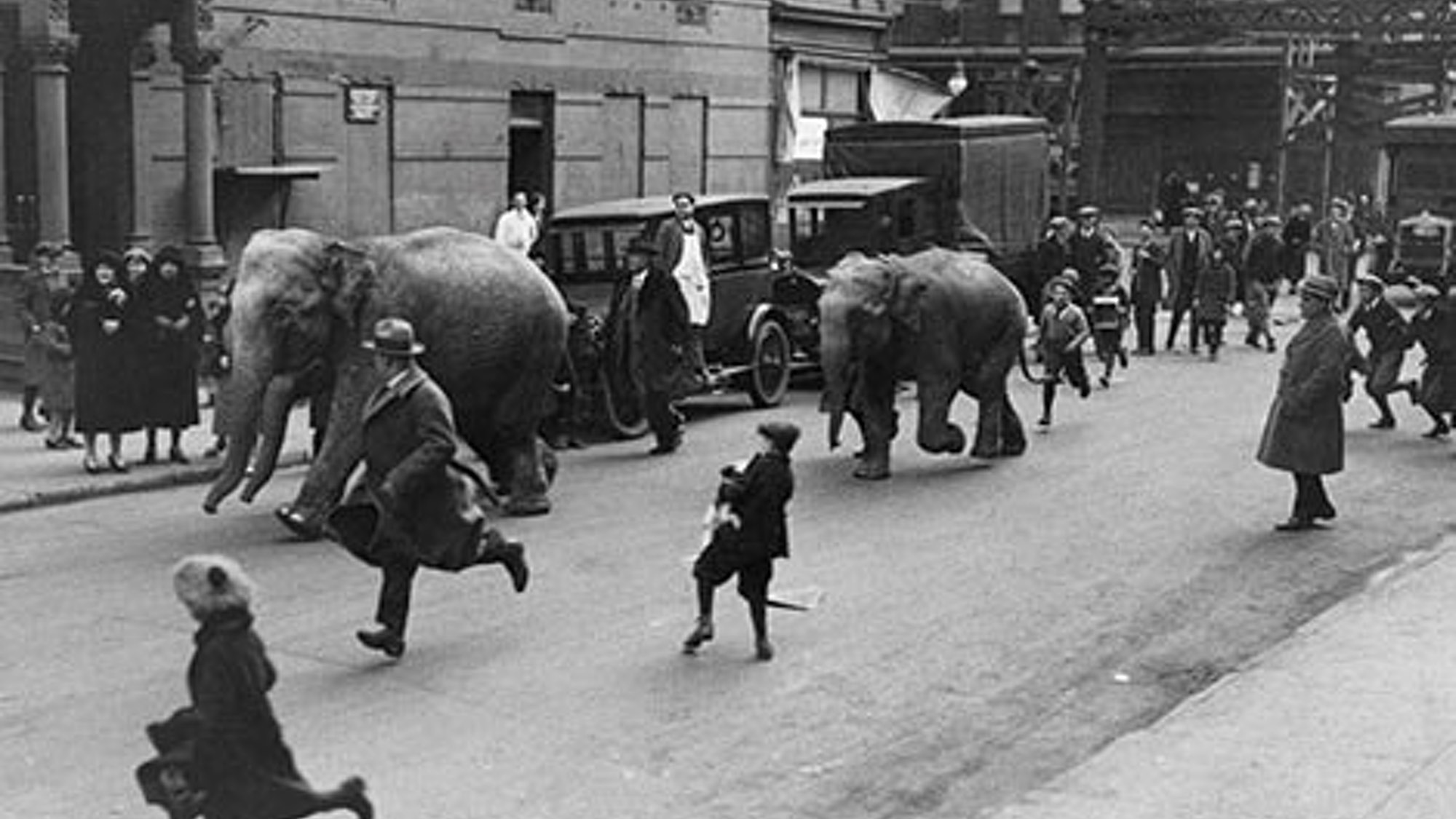

Photo is reportedly of a 1930 incident where a bunch of elephants escaped a vaudeville show in New York, but I can't confirm. If anyone has a link to the story, I'd love to hear about it.

If you'd like to read more about why platform teams may be slow, my friend Mark Headd and I once wrote quite a bit about it: The Platform Smells Playbook. Mark is wicked smart.

Published in Writing