Many years ago, armed with little more than a crude word processor and a take-on-the-world attitude, I embarked on a quest to become A Great Journalist. Day after day I fell bleary-eyed into early-morning classes, seeking knowledge. My words were going to make a difference.

In the end, I only became a Middling Journalist, but I did manage to pick up a few insights and aphorisms that have proven useful since. Few are as useful and true (if clichéd) as this:

Know your audience

My journalism days are long past, but I continue to find applications for that shopworn slogan. It's hugely applicable in design, of course, but also product management and engineering. And nowhere in engineering is it more applicable than when it comes to writing technical documentation.

Every day, engineering teams everywhere bicker endlessly about where to put their docs: Do we need a developer portal? Should they all be in Confluence? Do we need a Wiki?

They endlessly seek the Single Source of Truth, writing and re-writing docs hoping to create the one true version of their technical docs. But here’s the real truth: for most engineering teams and technical projects there will never be a Single Source of Truth because there is no single group seeking truth.

You have to know your audience, so start with the simple questions: Who will read these docs? Why? What do they hope to learn?

Just thinking about the audience for your documentation will put you ahead of most engineering teams, because most engineering teams don’t really understand – or completely misunderstand – the audience for their technical docs. Even fewer understand that they almost definitely have more than one audience for their documentation.

Nearly every engineering project will have at least two different audiences for their documentation.

At least two audiences. Probably three or four. Maybe more.

Know your audience(s)

Each of the audiences for your docs have divergent needs and desires. Without understanding that, your documentation will always be bloated, messy, and hard to understand. You don't know your audiences, so you’re not giving them what they need. If you’re like most teams, you’ll either give up and leave everything under-documented, or you’ll shotgun out ever-larger heaping piles of docs, few of which will ever be read, let alone usable to their audience.

Each of your audience needs documentation at a different fidelity, in a different location, to meet different needs. Your Single Source of Truth is wasting all their time. And yours.

You need to write the right documentation, for the right audience, in the right place. And that’s not a one-time thing. So who are the audiences? Allow me to pull back the curtain and shine a spotlight...

1. Engineers in the codebase#

This is probably you. And your team. And your future teammates. You are the folks reading and writing the code, actively developing it.

What you want (what you really, really, want) is documentation adjacency. You want the docs to be close to what you're reading or writing spatially, not in some far-off wiki, but also focused cognitively to the work at hand. In other words, you don't want or need a birds-eye view of the system, you need to understand this function, right here. And that's enough.

So it makes sense that these docs should live in the code, or as close as possible to the code it is talking about. I mean, you can't generally put comments in JSON, but you can, and should, put any docs you need explaining the JSON as near to it as possible, probably in the functions creating or consuming the JSON.

Also remember that you and your team will likely read the code far more than you will write new code, so document accordingly.

- Adjacency to code: high

- Granularity: high

- System-level understanding: low

- Explanation of benefits: low

2. Engineers leveraging the codebase#

This could be teams building on your platform, or consuming your API, or leveraging your open source project, or a million other things. Whatever they're doing, they have their own code to worry about, but for some miraculous, wondrous reason they want to use yours too. You should be flattered, and you should take good care of them by understanding and meeting their needs.

But if it's all engineers, what do they want that's different than what you and your team wants? A higher-level system view. They probably don't care about the individual functions and they almost definitely have no interest in reading your code to understand it. They want things like:

- how-to instructions to implement and get it running

- Understanding of how to interface with it

- Gotchas they should watch out for

- Code examples and snippets to show how things work

- Clear and honest documentation of limitations. If it's not going to do [thing] but they really need [thing] let's just get that out of the way up-front.

These folks don't want their docs in your code, because they don't want to read the code, but they probably want it pretty adjacent to wherever they go to get your code. Most times, that's probably the github repo, or someplace close to it. This is where you want to document the higher-level technical functions and APIs, and how engineers are expected to consume and use your codebase. It’s where documentation generators – SwaggerUI, Doxygen, Swimm, etc – may be most helpful.

- Adjacency to code: medium

- Granularity: medium-low

- System-level understanding: medium-high

- Explanation of benefits: medium

3. People understanding the codebase at a high level#

This is most likely to be stakeholders, prospective partners or customers, your product manager, a technical writer or even your marketing department. Whoever it is, they have a healthy interest in your codebase, but they’re more interested in what it does, rather than how it does it. Many times, they’re seeking enough understanding that they can then explain it to their own audience.

This group may be looking at the docs pretty far removed from the actual codebase, and that's OK. In fact, for this group, Confluence or some other system closer to where they work can make a lot of sense.

- Adjacency to code: low

- Granularity: low

- System-level understanding: high

- Explanation of benefits: medium-high

4. People using the product built on the codebase#

These could be your most valuable audience, but too often they're ignored by engineering completely and simply handed off to the marketing department.

This group has very little interest in the codebase. If they’re looking at it at all, it’s probably because they accidentally wandered into the Github repo from a link added by someone who didn’t understand the audience he was speaking to.

What this group wants to know is simple: can it solve their problem? As an engineer, you offload these conversations to another department at your peril: You know better than they do what your code can and can't do, so you are better equipped to take at least the first pass at documenting it.

Talk about the benefits with honesty and without hype. Someone will inevitably add additional hype downstream of your efforts. Before it gets there, though, you can have a real conversation about why you created the thing you created, who you created it for, and what it can do to make their lives better. The how is for another audience.

- Adjacency to code: very low

- Granularity: very low

- System-level understanding: medium

- Explanation of benefits: high

Putting it all together#

Writing docs for all these audiences sounds like a lot of work, but in practice it could lead to writing fewer docs that are more effective. If the docs aren't meeting the needs of the intended audience, and meeting them where they are, then throw those docs out and never update them again.

And the docs you are investing time in will have more clear value. Your team is happier. Your stakeholders and users are happier. Your product is more successful because the folks using it are happier and more able to solve their problems. For each audience, you’re focusing on their needs, and not weighing them down with extraneous baggage. They appreciate that.

In many cases you'll be moving the docs someplace more adjacent to the codebase, if not within it, which means keeping them up to date gets a lot easier: you update them when you change the code that's right there, rather than updating some far-flung wiki no one remembers to read.

Know your audience.

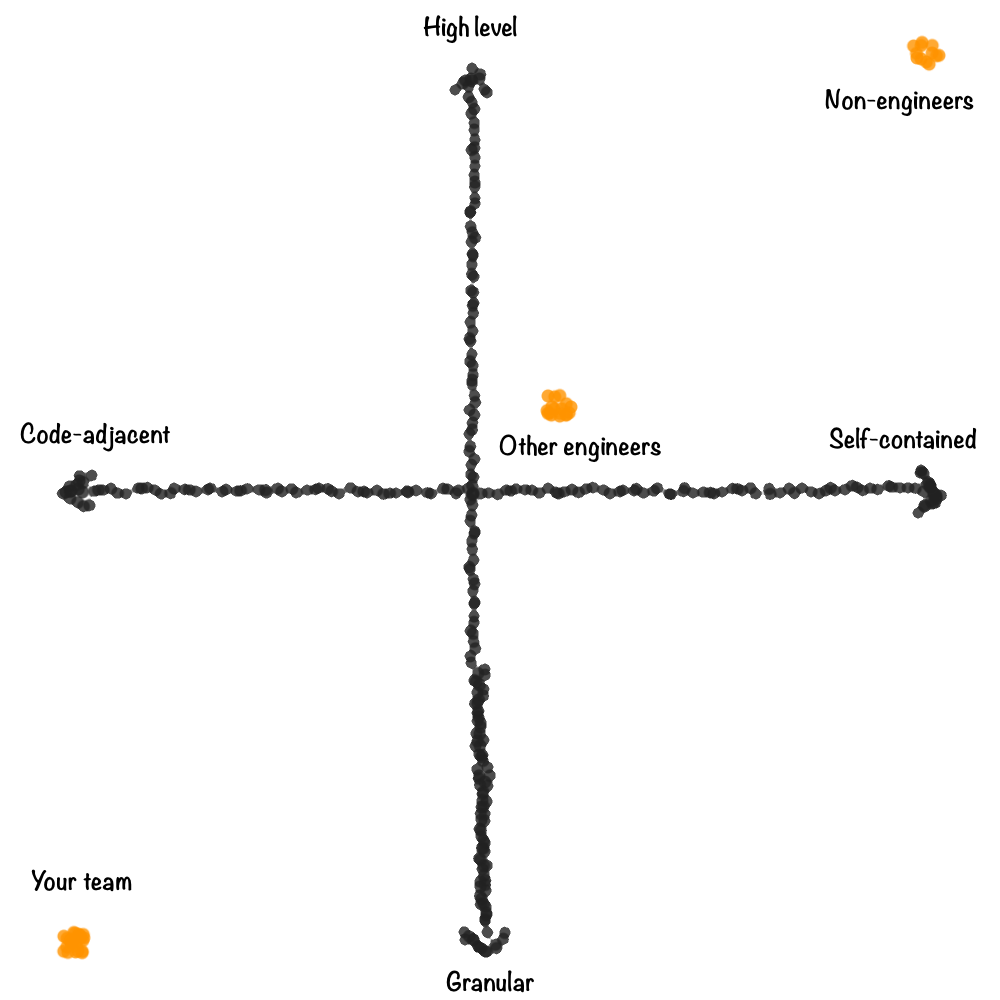

To help visualize all this, here’s a carefully crafted high-fidelity rendering I created:

With my thanks to Stacy Holmstedt, Jeff Triplett, Jennifer Wadella, Josh Chessman and others who helped me bounce these ideas around. If you’re interested, Daniele Procida built a framework on some similar ideas awhile back. Check it out at https://diataxis.fr/

Published